Want some easy tips to follow to make training that sticks? To create training workers will remember and apply on the job? To help you attain the business goals you’re trying to reach?

Although inspired by Malcolm Gladwell’s book The Tipping Point and written for a popular reading audience instead of exclusively for training professions, the book Made to Stick (more details about the book will come below, don’t worry) is a great source of information about current research into what makes things memorable and what causes people to act.

As trainers, we want to craft memorable training and we want training that workers will apply on the job. So you can see how the messages in this book will make your training better. It’s even a book you will notice a lot of training professionals referring to.

Interested in learning some of the tips from Made to Stick? If so, start by taking a little time to read the two selections below. As you read, ask yourself which you’re more likely to remember later–one or two days later, but even an hour or fifteen minutes later, too.

When you’re done we’ll cycle back and explain how this all relates to effective workforce training.

“A friend of a friend of ours is a frequent business traveler. Let’s call him Dave. Dave was recently in Atlantic City for an important meeting with clients. Afterward, he had some time to kill before his flight, so he went to a local bar for a drink.

He’d just finished one drink when an attractive woman approached and asked if she could buy him another. He was surprised but flattered. Sure, he said. The woman walked to the bar and brought back two more drinks-one for her and one for him. He thanked her and took a sip. And that was the last thing he remembered.

Rather, that was the last thing he remembered until he woke up, disoriented, lying in a hotel bathtub, his body submerged in ice.

He looked around frantically, trying to figure out where he was and how he got there. Then he spotted the note:

DON’T MOVE. DIAL 911.

A cellphone rested on a small table beside the bathtub. He picked it up and called 911, his fingers numb and clumsy from the ice. The operator seemed oddly familiar with his situation. She said, “Sir, I want you to reach behind you, slowly and carefully. Is there a tube protruding from your lower back?”

Anxious, he felt around behind him. Sure enough, there was a tube.

The operator said, “Sir, don’t panic, but one of your kidneys has been harvested. There’s a ring of organ thieves operating in this city, and they got to you. Paramedics are on their way. Don’t move until they arrive.” [Source: see note 1]

Now, the second:

“Comprehensive community building naturally lends itself to a return-on-investment rationale that can be modeled, drawing on existing practice,” it begins, going on to argue that “[a] factor constraining the flow of resources to CCIs is that funders must often resort to targeting or categorical requirements in grant making to ensure accountability.” [Source: see note 2]

OK, now that you’ve read them both, which are you more likely to remember? Why?

And how can you apply this to the training you create? Read on to learn how.

- Learning Management Systems

- Online Workforce Training Courses

- Custom Workforce Training

- Incident Management Software

- Mobile Training Apps

Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, a Book by Chip & Dan Heath

The two excerpts above are both drawn from the beginning of the book Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die by Chip & Dan Heath. Their point in including the two written selections was to give an example of something that’s easy to remember (the organ thief story) and something that’s not (the comprehensive community building discussion). And then to get you thinking why one’s more memorable than the other.

You agreed with us, and with the brothers Heath, that the organ heist story was more memorable, right?

If so, let’s move on and learn more about the book and see how we can apply it to training. If not, maybe it’s worth reading the two samples one more time and trying that test again…

What the two brothers Heath set out to do in writing this book is to determine what makes some things memorable (and what others are so easily forgotten). In doing so, they came up with a list of six characteristics:

- Simplicity

- Unexpectedness

- Concreteness

- Credibility

- Emotions

- Stories

The Heaths provide an easy way to remember these items, too, borrowing the first letters to spell the word: SUCCES(s).

It’s worth noting that they don’t believe these are the only things that make something memorable, and they don’t believe a specific communication has to have all six elements in order to be memorable.

So let’s take a quick look at the key points in this book and see how they are related to workforce training issues.

The Curse of Knowledge–When Knowing Something Well Leads to Bad Training

The Heath brothers noted one “curse” that makes it harder to create something memorable. They call it “The Curse Of Knowledge.” That’s maybe not what you were expecting–after all, we typically think of knowledge as a good thing, right?

By this, they mean that it’s often harder for someone who knows something very well to communicate something about that topic to a person who isn’t familiar with the topic and still make it memorable. And so that curse of knowledge makes it hard for subject matter experts and trainers, who are trying to deliver information to workers, to effectively transfer the information.

As a trainer, you probably already know that to create effective training, you’ve got to start by putting yourself in the trainees’ shoes. By trying to imagine how they’ll approach the training based on their current, existing knowledge of the training topic, you can then create training that’s more appropriate to them and that they’ll learn/remember/apply more effectively.

That’s one of the reasons we do our training needs analyses, right?

On the flip-side, if you don’t step into the employee’s shoes (and minds) for a minute, it’s easy to create training that flies over their head, that’s based on assumptions that they know things they don’t know, that leaves important stuff out, that moves too quickly, or that jams too much information in.

This can be a problem for any trainer. It’s an even bigger problem when you’re working with a subject matter expert (SME) who really knows and loves the stuff.

Here’s how the Heath brothers discuss what they call the “Curse of Knowledge:”

“This is the Curse of Knowledge. Once we know something, we find it hard to imagine what it was like not to know it. Our knowledge has “cursed” us. And it becomes difficult for us to share out knowledge with others, because we can’t readily re-create our listener’s state of mind….

There are, in fact, only two ways to beat the Curse of Knowledge. The first is not to learn anything. The second is to take your ideas and transform them.” (See note 3)

And that’s what the Heath brothers think you can do–transform your knowledge and ideas so they’re more memorable–by using the tips in their book.

Which we’ll start discussing now. We promise. 🙂

Training that Sticks Tip 1: Simplicity

The first technique is simplicity.

By this, the Heath brothers note they really mean two things:

- Identifying a single, critical, “core” message you’re trying to communicate

- Presenting that “core” message in a concise, “compact” manner

As learning professionals, this makes sense to us. In fact, many trainers commonly use an acronym for this idea: KISS, which stands for “keep it simple, stupid!”

We know that before we create training, we’re supposed to create one or more learning objective. The learning objective(s) is the essential, absolutely “core” message of the training. That’s what our employees need to know, and that’s what our training should communicate (and only that).

Want more information about learning objectives? Download our free Learning Objectives Guide.

Not only that, we know we’re supposed to keep our training short (in fact, there’s a big movement toward “microlearning” going on right now). This includes not only the earlier note about identifying learning objectives and creating training that’s about nothing but the learning objective, but also editing in a merciless fashion to present that information very briefly.

For example, check out our Tips for Writing Training Materials, which notes the importance of keeping things brief.

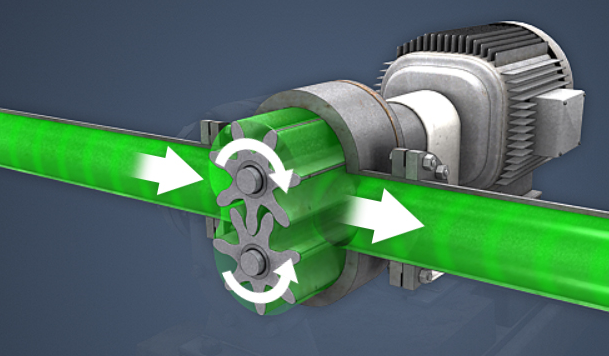

At Convergence, we do a lot of things to keep our training simple. We create and focus on learning objectives, of course, and we write and then edit our materials to cut out as much deadweight as possible. Another thing we do is has to do with the visual nature of our training materials. Although we have the ability to make very detailed, life-like visual training materials, and we DO that when the circumstances call for it, we also have the ability to “strip away” a lot of details from the environment that don’t support the core message of our training, as shown in the still image below.

An example of keeping it simple from an eLearning course on valves.

Proverbs as a Model of Simplicity and Memorable Communication

The Heath brothers give some tips for communicating simply, too. For one, they suggest looking at proverbs as a good example. Proverbs are effective because they:

- Are short

- Use figurative language–figurative language is symbolic language that is less concerned with the literal meaning of the words used and more concerned with using terms to show relationships between ideas

- Use descriptive language that appeals to the senses (Yep, we mention the importance of descriptive language our Tips for Writing Training Materials article, too)

Consider this famous proverb which you’ve probably read before, and which you probably also remember and can easily state in your own words.

And again I say unto you, It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God. (Source: See note 4)

Short? Check–32 words to discuss economics, eternity, and divine salvation.

Figurative language? Check–we’re talking about camels passing through the eyes of needles, right?

Descriptive language that appeals to the senses? Check–it’s easy to visualize a camel trying to get through the eye of a needle–this isn’t abstract.

Here’s another–test it for yourself.

The fathers have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge. (Source: See note 5).

Ask yourself–is it short; does it use figurative language; does it use descriptive language that appeals to the senses; and, most importantly, is it memorable?

Our point here isn’t to give you a religion lesson, but to demonstrate how effectively these proverbs use figurative and descriptive language to clearly communicate complicated and abstract points to create sayings that have been remembered for thousands of years. No matter your religious beliefs, that’s impressive communication, and impressive memorability.

Figurative Language: Analogies, Metaphors, Similes, and More for Memorable Training

Expanding on their tip to use figurative language, the Heath brothers call out in particular the use of:

- Analogies

- Metaphors

Analogies and metaphors are types of figurative language, after all.

You can take that recommendation to use analogies and metaphors on faith (ha!-no religion pun intended), or you can look further into why the Heaths recommend this. They (and other learning experts) note that people “process” new information by integrating it with existing information that’s “stored” in the brain in something brain experts called schemas. Using analogies and metaphors aids this process.

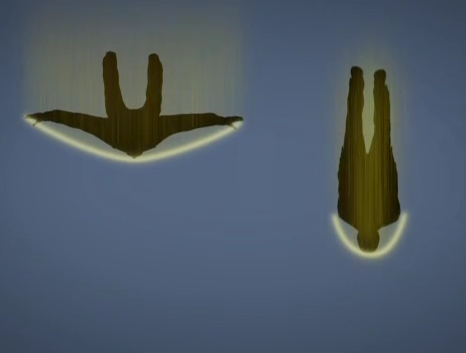

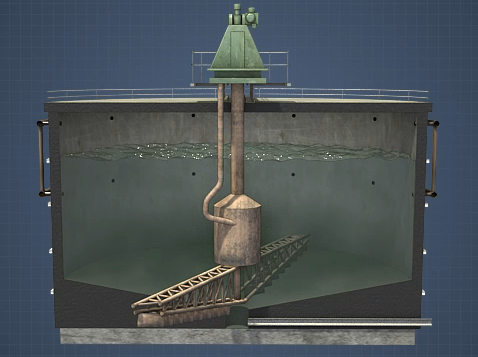

Here’s an example of a “visual metaphor” from a training course we made. The image uses an idea people are probably familiar with–a skydiver falling through the sky–to help the learners understand an industrial process in which solids settle through a solution.

This still from an eLearning course about paper manufacturing uses a visual metaphor to explain an industrial process that’s too small to see with the naked eye and that takes place inside a closed vessel.

Read our article on using analogies, metaphors, similes, and comparisons in training

Read our article on adult learning principles, which notes that adults come to training with pre-existing knowledge and life experiences

Read more about how we learn, including schemas in long-term memory (this specialized term is one of the few that the Heaths keep coming back to again and again, partly because it’s so important in how people learn, and so it may be worth getting to know better)

Say It Up Front: Don’t Bury the Lead

The final tip the Heath brothers provide for keeping things simple is one they borrow from journalism: don’t bury the lead.

What this means is to put the important information up front, not later. Let people know what the training will cover right at the beginning. Don’t keep them in the dark.

Training that Sticks Tip 2: Unexpectedness

The next of the six tips is unexpectedness. Give the employees something they weren’t expecting.

You’ve already seen an example of this. Remember when the Heaths said that the Curse of Knowledge is an enemy of good training? That’s unexpected, right?

To put that in learning terms, and to return to the one bit of learning jargon the Heath brothers consistently return to in the book, what you’re doing here is creating a “disruption” with the employees’ existing schema (remember, that basically means what they already know or think they know about the topic).

Here’s a reminder about how we learn and where schema fit in.

Here’s a reminder that one of the adult learning principles is to remember that adults come to training with a lifetime of knowledge and experience–in this case, you’re presenting information that, at least initially, challenges what they know.

Here’s a simple example of using an element of unexpectedness from a Convergence Training safety training course. We included the “Jolly Roger” beloved by pirates everywhere in this danger symbol. This momentarily surprises and captures the attention of learners.

A simple example of an unexpected visual in a safety eLearning course.

And here’s another example, from our H1N1 Flu course. The cartoon-ish H1N1 flu virus isn’t what workers expect to see when they launch a course about flu prevention. That unexpected playful nature gets their attention and their buy-in, at least momentarily.

This image from a Flu Awareness eLearning course represents the flu virus in an unexpected manner that grabs the attention.

Surprise Then Make Sense

However, it’s not as easy as simply being shocking and gimmicky. I could wear unexpected, outrageous clothing in a training session or deliver training in the form of interpretative dance, both of which would be unexpected but neither of which would guarantee that the training’s memorable.

Instead, the Heath brothers recommend you be unexpected while also:

- Avoiding gimmickry by making sure your unexpectedness still supports your key message

- Providing insight by surprising people and then helping them make sense of the information and see how it’s all connected

Here’s a four-point plan that the Heath brothers suggest for doing this:

- Identify the core, central message you need to communicate

- Figure out why employees don’t know or aren’t doing it now (why doesn’t it happen naturally) and figure out what’s counterintuitive about the core message

- Communicate your message in a way that is unexpected to employees in a way that points out the counterintuitive aspect you’ve identified (the Heath brothers call this “breaking their guessing machine,” and by this they mean disrupting their current schema)

- Help them make sense of the unexpected/contradictory information to create a new, sensible body of knowledge of the topic

An Example of Surprise then Sense

Want an example of surprising someone with a counterintuitive message and then turning around to make sense of the surprise?

I can give you one drawn directly from the book. Somewhat unexpectedly, the book mentions that

“Common sense is the enemy of sticky messages” [Source: See note 6]

That seems counterintuitive, right? Isn’t effective communication based in common sense?

But no, the Heaths (sensibly) point out. If you get up in front of a training audience, and say something that’s entirely common sense, you’ll never grab their attention. They may nod their heads knowingly, but even then, you’re at a high risk of in-one-ear-and-out-the-other ear. And that’s if you’re lucky, because the fact of the matter is, they may never give that common sense statement of yours even a moment’s thought–after all, did you see that pretty bird outside the window?

Catching Attention Isn’t Enough: You Must Maintain that Attention, Too

Getting the employee’s attention at the beginning of training is good. It’s a necessary precondition for training.

But attention isn’t constant. Just because you have a person’s attention for a moment doesn’t mean you’ll keep it.

And, as a result, you can’t just rely on dropping some unexpected message on your employees during training, as if that’s going to do all of the work for you.

In short, once you’ve got their attention, you’ve got to work to keep their interest. What does the book suggest?

You can keep employees attention during training to keeping them aware of the gaps in their knowledge. For example, you can present a mystery to the employees and ask them to solve it. When they recognize they don’t know the information, that will renew their attention and drive them forward in an attempt to close that knowledge gap (the Heath brothers call this the “gap theory of curiosity”).

Here’s a reminder that the gap theory of curiosity is consistent with adult learning principles and the focus on active learning experiences.

Scenario-based learning can be a great way to make use of the gap theory of curiosity.

The gap theory of curiosity is also very consistent with the primary messages in Julie Dirksen’s wonderful book Design for How People Learn.

Training that Sticks Tip 3: Concreteness

The next tip is to present your training in concrete, not abstract, terms.

By concrete, he means things that people can:

- See or visualize

- Hear

- Taste

- Touch

- Otherwise examine with the senses

The tip to be concrete has two great benefits, according to the book. As the Heath brothers explain:

“Of the six traits of stickiness that we review in this book, concreteness is perhaps the easiest to embrace. It may also be the most effective of the traits.” [Source: See note 7]

To put that in concrete terms, that’s a lot of bang for the buck. You get a lot more “memorability” for something that’s easy to do. Win/win.

Fables as Examples of Concrete Communication

After having turned to proverbs as an example of simplicity, the book presents fables as an example of concreteness (you’ll notice both proverbs and fables use figurative and descriptive language).

For example, consider the two selections below, each drawn from the book. Which of the two versions of the same basic message is more memorable?

Version One:

“One hot summer day a fox was strolling through an orchard. He saw a bunch of grapes ripening high on a grape vine. “Just the thing to quench my thirst,” he said. Backing up a few paces, he took a run and jumped at the grapes, just missing. Turning around again, he ran faster and jumped again. Still a miss. Again and again he jumped, until at last he gave up out of exhaustion. Walking away with his nose in the air, he said: “I am sure they are sour.” It is easy to despise what you can’t get.”

Version Two:

“Don’t be such a bitter jerk when you fail.”

[Sources: see note 8]

You may recognize the first version as Aesop’s famous fable “The Fox and the Grapes.” The second version is the Heath brothers’ attempt to convey the same message in a different manner.

What’s more memorable? The first, right?

And why? Partly because it’s phrased in concrete language. Consider the use of concrete terms: hot summer day; orchard; bunch of grapes; ripening; grape vine; quench my thirst; backing up a few paces; took a run and jumped at the grapes, just missing; turning around; ran faster and jumped again; again and again he jumped; gave up in exhaustion; walking away; nose in air; sour.

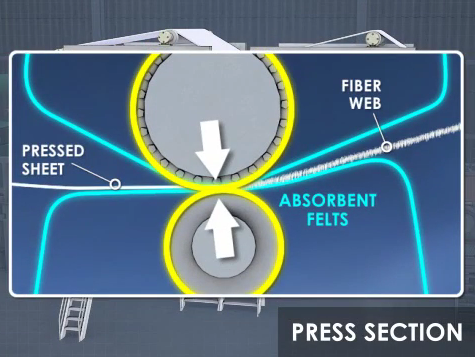

At Convergence, we think one of the great benefits of training that incorporates visuals is that it’s very concrete and appeals to the senses. And not just to the senses, but to our sense of sight, because we’re very much visual creatures. The still image below, taken from a course on papermaking, is an example of that.

An example of visual training that appeals to the senses from an eLearning course on papermaking (of course, there’s also audio narration that accompanies this image).

The Velcro School of Training Stickiness

Why does being concrete make communication (and training) more memorable?

It’s because of how we process information and store it in our brains (and those schema we talked about earlier). And because, as we also mentioned earlier, when we encounter new information, we process it by trying to connect it with existing information.

The more potential points of connection that new information has, the more opportunities it has to connect to information that’s already in your brain. And using concrete communication aids in this.

In that sense, it’s like Velcro, with the concrete details of your communication acting as the tiny hooks. Or, as the Heaths explain nicely:

“Memory, then, is not like a single filing cabinet. It is more like Velcro. If you look at the two sides of Velcro material, you’ll see that one is covered with thousands of tiny hooks and the other is covered with thousands of tiny loops. When you press the two sides together, a huge number of hooks get snagged inside the loops, and that’s what causes Velcro to seal.” [Source: see note 9]

This Velcro analogy is a nice concrete explanation of an otherwise abstract idea, don’t you think?

For a similar comparison, check out Julie Dirksen’s great book Design for How People Learn which suggests thinking of our brain as a closet with lots of stuff stored in it and lots of different connections running between the items. I’m not doing her book justice with this top-of-my-head description, but check out the book and you’ll see what I mean-it’s a point that’s “stuck” with me since I read her book some years ago.

Abstraction Is the Enemy of Concrete Communication

If concrete communication is good, it’s opposite-abstraction–is bad.

As the book explains, being able to think about something abstractly is something experts can do and novices can’t.

“Why do we slip so easily into abstraction? The reason is simple: because the difference between an expert and a novice is the ability to think abstractly.” [Source: See note 10]

If you give that quote above a second thought, you’ll see why abstraction is out of place in training. When you’re training, you’re working with people who are closer to the novice end of the spectrum on that given topic. What’s the point of delivering training to people who are already experts on the topic–they already know the stuff, right? And so abstraction, a form of communication that’s helpful when experts communicate with experts, isn’t useful when you’re delivering training to people who aren’t experts.

Or, as the book puts it:

“Concrete language helps people, especially novices, understand new concepts. Abstraction is the luxury of the expert. If you’ve go tot teach an idea to a room full of people, and you aren’t certain what they know, concreteness is the only safe language.” [Source: See note 11]

Jargon, Buzzwords, Acronyms: Avoid ’em When Possible

Specialists talk to each other in specialized language. That often includes things like buzzwords, jargon, and acronyms.

Savvy readers may notice that the use of jargon, buzzwords, and acronyms is an example of the “Curse of Knowledge” mentioned at the top of this article. These are not examples of concrete communication. They are shorthand that makes communication between experts easier.

So–you guessed it: don’t use buzzwords, jargon, acronym, and similar specialized language in training. Try to put the same ideas into everyday, concrete, descriptive terms instead. Or, if you determine the employees must learn to use the specialized language, be sure to clearly explain what they mean–don’t just start using them and assume folks will catch up with you.

One of the points in our How to Write Training Materials article is to avoid specialized language like this.

Focus on the Needs of The Trainees

Another way to present our training messages in a more concrete way, which in turn will make them more memorable and more likely to be used on the job, is to focus your message on the needs of the employees.

This may seem like a no-brainer, but many people jump into training development and training delivery without giving much thought to what information the employees want and need to do their job.

Remember to do your training needs analysis to find out more about what employees need to know to do their job; and remember, the adult learning principles include the fact that adults want training that’s relevant and task-oriented.

You might also want to check out this crash course on design thinking.

Training that Sticks Tip 4: Credibility

By now, we’ve mentioned several times that one of the adult learning principles is that adults come to training with a lifetime of their own experiences, ideas, thoughts, options, and–perhaps most importantly–habitual, ingrained behaviors.

And that means if we are going to influence their opinions, win them over to a new viewpoint, get them to remember new information, and get them to change their behavior on the job, we’ve go to establish credibility.

Or, as the book puts it:

“We can’t construct a PowerPoint presentation that will nullify people’s core beliefs…If we’re trying to persuade a skeptical audience to believe a new message, the reality is that we’re fighting an uphill battle against a lifetime of persona learning and social relationships.” [Source: see note 12]

So how do we do that?

One way is to appeal to authorities.

Credible Authorities

If you’re an authority, or if you can have an authority deliver you’re training, you stand a good chance of seeming credible.

According to the book, authorities come in two flavors:

- Subject matter experts: People who really know their stuff on the training topic. This is a common method of gaining credibility in training. For example, in safety training, many workers like to receive safety training about their work processes from someone with many years of experience working at that site.

- Celebrities: Chalk this up to the desire to “be like Mike” (Michael Jordan, that is). For psychological reasons beyond the scope of this article, people will buy the underwear that Michael Jordan says he wears, or will wear the perfume that Kim Kardashian says she wears, because they want to be like these celebrities. In most cases, we assume you don’t have access to NBA superstars or social media/reality TV “stars,” but sometimes trainers do have an air of celebrity, especially within a given niche, and there’s nothing wrong with taking advantage of that when you can.

At Convergence, we work very closely with subject matter experts to help build that credibility. When employees at a manufacturing facility open their learning management system and watch one of our courses on an industrial process, the detailed visual and verbal explanations very quickly help them determine that we “know our stuff.”

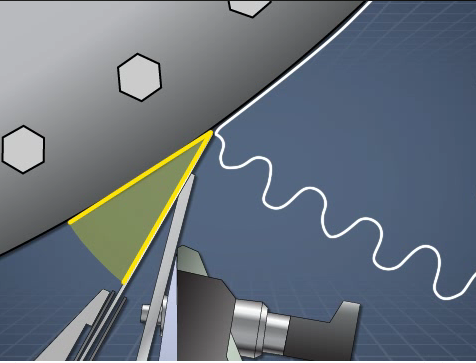

Training created or led by people with great knowledge of the subject matter, such as this eLearning course on pulp production, is generally considered credible.

Credible “Anti-Authorities”

An anti-authority is someone you wouldn’t immediately think of as being credible on a topic, but who is, typically because of circumstances in their life.

The example that the Heaths use in the book is a woman named Pam Laffin. She’s not a subject matter expert on health issues, she’s not a celebrity. But she was a 29-year old mother of two who started smoking at 10, had emphysema at 24, suffered a failed lung transplant, and starred in an influential series of TV commercials warning about the hazards of smoking before she died at the age of 31 from complications related to smoking. That series of commercials had a dramatic effect on smoking rates due to the circumstances of her life (her experiences smoking and the health consequences) and the stories she tells. She’s a credible anti-authority because smoking killed her.

You can use anti-authorities like this in a similar way. Safety training is somewhat famous for this. Here’s a powerful example: the video “Dangers of Hot Work” by the Chemical Safety Board.

This video by the Chemical Safety Board includes a credible anti-authority who suffered a terrible accident on the job and was willing to share his story.

Incorporate Compelling, Relevant Details that Support Your Core Idea

You can also gain credibility if you include concrete, detailed knowledge.

As the book notes:

“A person’s knowledge of details is often a good proxy for her expertise. Think of how a history buff can quickly establish her credibility by telling an interesting Civil War anecdote. But concrete details don’t just lend credibility to the authorities who provide them; they lend credibility to the idea itself. The Civil War anecdote, with lots of interesting details, is credible in anyone’s telling. By making a claim tangible and concrete, details make it seem more real, more believable.” [Source: see note 13]

The takeaway? While it’s important not to drown your trainees in a sea of details, especially ones that may be of interest only to you, showing that you know your stuff and/or have “chops” (as the jazz guys say) goes a long way.

The Heath brothers make that same point about ensuring your details are relevant. More specifically, they caution:

“But what should also be added is that we need to make use of truthful, core details. We need to identify details that are as compelling and human as the “Darth Vader Toothbrush” but more meaningful–details that symbolize and support our core idea.” [Source: See note 14; as concerns the “Darth Vader toothbrush,” that’s a detail shared in an example the Heaths use in their book]

When we make a course at Convergence, we make sure we know that core message, that we know all the relevant details that support that message, and that we present those essential details to learners completing our training courses.

Training with details, but only the relevant details, as shown in this paper manufacturing eLearning course, is generally considered credible and is therefore more likely to be effective.

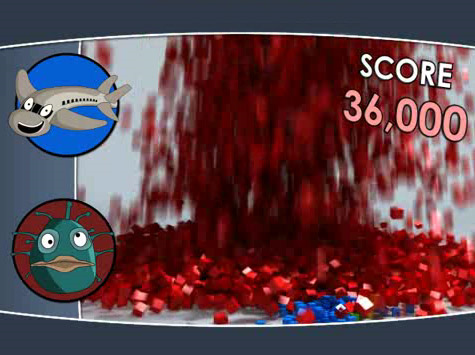

Use Statistics–But Don’t Flood Them With Figures and Data

Take a moment and ask yourself: how many times have you attended a training and been presented with statistics?

1,237? No, we kid, because we wanted to use a statistic.

But using statistics in training, especially to try to get attention at the beginning, is pretty common, right?

And that’s because people think using statistics makes the training seem relevant, necessary, and/or based in “real world” realities.

It’s a good idea, but it’s often carried out poorly. And that’s because nothing inspiring, motivational, or memorable about pure numbers (apologies to the math whizzes out there). When presented with raw data and pure numbers, people tend to do two things: (1) forget them quickly and (2) change no behaviors.

Instead, if you present statistics in the form of some kind of relationship, you’ve got a better way to communicate with people, to make them remember, and to change their behavior. A classic example is telling people who are afraid to swim in the ocean because of sharks that they have a better chance of dying after being hit on the head by a coconut.

Here’s how the Heaths put it:

“Statistics are rarely meaningful in and of themselves. Statistics will, and should, always used to illustrate a relationship. It’s more important for people to remember the relationship than the number.” [Source: see note 15]

This is something we try to do at Convergence. For example, in the H1N1 flu virus course mentioned earlier, we give some statistics to explain how many people die of the flu each year. However, we don’t just give raw numbers. Instead, we do this NOT ONLY BY comparing flu-related deaths to the number of deaths caused by other things people are frightened of (such as sharks or, as shown in the image below, airplanes) but also by visually representing the deaths with colored cubes–the red cubes shown below represent deaths from the flu, which easily, literally, and very visually dwarf the number of deaths caused by other means (if you look closely you can see a small number of blue and green cubes, which represent deaths from sharks and airplanes, as well).

We try to present statistics in our eLearning courses in a concrete manner and in a way that expresses a relationship.

Another tip the Heaths have for using statistics is to try to change them from abstract numbers to some form of more concrete information presented at a human scale that incorporates already existing knowledge (those schemas again).

The “Sinatra Test”

To begin this discussion, it helps to listen to the Frank Sinatra song “New York, New York.”

We’ve provided it below for your listening (and viewing) pleasure. Listen to as much as you want, but for our purposes, you really only need to listen to the first 1:36, meaning you can stop after you hear the chorus the first time.

Did you hear it? “If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere!”

The Heaths refer to this kind of sentiment as “The Sinatra Test.” Something that passes the Sinatra Test is something that makes a statement like one of these:

- If I can do it there, I can do it anywhere

- If I can do it under those circumstances, I can do it under any circumstances

- If I can do it with them, I can do it with anyone

- If I can do it to them, I can do it to anyone

Get it? The point is to say if something can happen under very difficult circumstances, perhaps the hardest circumstances of all, then it can be done in all circumstances.

This tip is aimed less at getting people to remember your message and more at inspiring them that it can be done and therefore they should do it, but it’s still important for training.

Training that Sticks Tip 5: Emotions

The fifth of the six tips is to appeal to a person’s emotions if you want them to remember something and, most importantly, to act on the information to do something and/or to change a behavior.

The enemy here is analysis, which is similar to that abstraction we’ve discussed earlier, and which is also something that happens if you rely on pure raw numbers and data in your use of statistics.

Or, as the book notes:

“The researchers theorized that thinking about statistics shifts people into a more analytical frame of mind. When people think analytically, they’re less likely to think emotionally. And the researchers believed it was people’s emotional response…that led them to act.” [Source: see note 16]

A simple example from a course Convergence created is this menacing-looking, forbidden tornado in our course on emergency action plans. The dark, threatening funnel cloud is enough to get our brains pushing some “danger and fear emotions” around.

Visuals, such as this menacing tornado in an Emergency Action Plan eLearning course, can help to create emotional responses during training.

And here’s another, from a course on machine guarding, which gets the “ouch, I don’t want that to happen to me!” emotions going without resorting to unnecessary or disturbing gore.

This image from an eLearning course on Machine Guarding creates an “Ouch!” emotion without resorting to gore.

Invoke Self-Interest: What’s In It For Me?

The Heaths give several tips for involving appeals to employees emotions in training that will, in turn, help change their behaviors on the job. One of the most notable is an old Trainers 101 Standard: Address the “What’s In it for Me (WIIFM)?”

As the Heaths put it:

“We make people care by appealing to the things that matter to them. And what matters to people?…People matter to themselves. It will come as no surprise that one reliable way of making people care is by invoking self-interest.” [Source: see note 17]

Even if this isn’t a stellar endorsement of our being a species devoted to altruism, if you give it some thought, it probably rings true.

Of course, “What’s In It for ME?” is nothing new to trainers. And it’s baked into the adult learning principles, with the points about:

- Making training relevant

- Appealing to the goal-oriented nature of adults in training sessions

- Employees learning when they’re motivated to learn

So obviously, your training should:

- Be something that truly will be useful and/or benefit the employees

- Include an explanation of why the training is useful/relevant/beneficial

Subtle Language Shift: Use the Second Person

In addition, one subtle way to make training have more emotional resonance, to appeal to your employees’ self interest, and to get them to adopt the training message is to write and/or speak in the second person (addressing employees as “you”) instead of using the third person (talking about “the employee”) and/or simply not talking about the employees at all (for example, focusing purely on a work process, equipment, or machine and never mentioning the human aspect).

We give this tip about the importance of addressing employees during training by using the second person in our article on writing training materials, and it’s something we use in our own courses.

Invoke Interest of and Association with a Larger Group

But if all that emphasis on WIIFM? and self-interest made you a touch depressed about our state as a species, there’s hope. Because the Heaths mention that an even important driver, and one that can even overpower pure self-interest, is group association and group identity.

By this, they mean that people make decisions based on what’s best for a group they identify with (for example, people of my profession or people who work here) or that they see as the kind of decision that people in groups they identify make (for example, “I’m going to do this because that’s what self-respecting members of my profession do”).

Here’s how the Heath brothers put it:

“It assumes that people make decisions based on identity. They ask themselves three questions: Who am I? What kind of situation is this? And what do people like me do in this kind of situation?

Notice that…people aren’t analyzing the consequences or outcomes for themselves. There are no calculations, only norms and principles. Which sofa would someone like me-a Southeastern accountant-be more likely to buy? Which political candidate should a Hollywood Buddhist get behind? It’s almost as if people consulted an ideal self-image: What would someone like me do?” [Source: see note 17]

Interestingly, as a training provider, we often hear about this effect from our customers. For example, not that long ago a company that was based in Hawaii and that manufactured corrugated board (that’s cardboard to you and me) began using our learning management system (LMS) and our safety/EHS training courses. Because they were a pretty new company, they really didn’t have much of a training program or safety training program before.

About a year after we began working with that customer, we were talking with the training manager on the phone. She explained to us that a culture change had taken place, and that employees were now taking the messages from the safety training materials and proactively applying them as a group on the job. The difference, the training manager noted, was that they had transformed from a group of individual workers making corrugated board to earn a paycheck and pay their bills to a group of people who all worked together at the same site and were dedicated to creating a safer workplace for the working community as a whole (for more on this story, read this article–it’s the first of the three companies profiled).

Training that Sticks Tip 6: Stories

The sixth and final tip for making training more memorable, and for making it more likely to cause employees to change their behavior on the job, is to use storytelling during training.

As humans, we’re hardwired to listen to and appreciate stories. Think back to ancient history and all the oral storytelling traditions–the Epic of Gilgamesh, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, native American oral histories, and so on. But maybe you think that’s all a thing of the past, and it doesn’t apply to our hyper-modern, social-media driven world of today? But then what do you make of the popularity of The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Downton Abbey, Mad Men, and even Serial.

The point is, we like stories. So maybe they’d be helpful in training? The Heath brothers believe they are, and they make a convincing point. A point that focuses on action, which is of course the real goal of all training:

“The story’s power, then, is twofold: It provides simulation (knowledge about how to act) and inspiration (motivation to act). Note that both benefits, simulation and inspiration, are geared to generating action. In the last few chapters, we’ve seen that a credible idea makes people believe. And emotional ideas makes people care. And…[now, while discussing storytelling-editor]…we’ll see that the right stories make people act.” [Source: See note 18]

Stories Make People Active Participants and Learners

Take a moment and think about what you do when you’re listening to a good story. The storyteller is proceeding, moving forward, and in the meantime, you’re actively working things out, trying to anticipate things, and basically trying to “solve” the story. In other words, you’re an active participant in the storytelling process. Without you, the audience, it’s fair to say there is no real story, since by listening and making sense of it, you constructed at least part of the story if not the whole thing (sounds like college and deconstruction, I know, but at it’s root, it’s a simple and basic idea).

The same is true when a trainer tells a story during training. The employees don’t just passively sit back and soak in the story. They are active participants in the storytelling process and play an active role in creating the story’s meaning. And that means that if a story presents a problem or challenge they may have to face on the job, they’ll be actively trying to solve theproblem themselves in their mind as the story unfolds. And that turns training that might have been presented as a boring, passive, and ultimately ineffective lecture into an engaging, active, and ultimately effective learning experience.

As the Heaths put it:

“Why is this story format more interesting? Because it allows his lunch partners to play along. He’s giving them enough information so that they can mentally test out how they would have handled the situation. The people in the room who weren’t aware of the misleading E053 code have now had their “E053 schema” fixed. Before, there was only one way to respond to an E053 code. Now, repairmen know to be aware of the “misleading 3053″ scenario.” [Source: See note 19]

Stories are Low-Tech Simulations

Of course, you can’t just tell any story. For example, if I’m delivering a training to teach manufacturing workers about 5S, I can’t just start telling them what happened in the most recent episode of Better Call Saul.

The story has to be about our core training message. And to be especially effective, it has to put the knowledge the training is intended to convey into a work-like framework. By being relevant to work scenarios, and allowing for the worker to be an active participant in solving a very low-tech “simulation,” stories can deliver a tremendous bang for their buck in terms of training effectiveness. As the book puts it:

“This is the role that stories play-putting knowledge into a framework that is more lifelike, more true to our day-to-day existence. More like a flight simulator. Being the audience for a story isn’t so passive, after all. Inside, we’re getting ready to act.” [Source: See note 20]

Want some good examples of this? Check out the following:

- The Broken Coworker eLearning course

- The Connect with Haji Kamal eLearning course

You can also read this article for more about scenario-based learning and simulations.

Stories Inspire People to Act

As we’ve demonstrated, people like listening to stories.

But that’s not all that stories do–provide idle entertainment. Some stories inspire people to go out and make changes in the world (or just to change their own behaviors).

Here are a few easy examples from American history that you’re probably already familiar with:

- The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin is often said to have been one of the things that led America into the Civil War. When Abraham Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, he is reported to have said “‘So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!” [Source: See note 21]

- The novel The Jungle by Upton Sinclair is often said to have played a major role in the development of regulations in the American food industry.

- The TV miniseries Roots played a major role in changing race attitudes and behaviors in 1970s America.

We’ve made this point before, but training isn’t about passing along knowledge. It’s about changing behaviors of employees so they’ll perform a specific task at work. If part of the problem with getting workers to perform that task is motivating them to want to do it, then the inspiring nature of stories can be a great aid.

Common Plots or Structures of Stories

What are the best kind of stories to use to make your message memorable and to inspire people to act?

The Heaths offer three common plots in their book as suggestions: [Source: see note 21]

- The challenge plot: The “hero” of the story overcomes a challenge. The book’s example is the Biblical story of David v. Goliath.

- The creativity plot: The “hero” solves a problem in an innovative way. The book’s example is the story of Sir Isaac Newton and the apple that falls on his head; a similar, well-known story from the history of science is the story of Archimedes yelling “Eureka” in his bathtub.

- The connection plot: A story about people who develop a relationship that bridges a gap. The book’s primary example is the Biblical tale of The Good Samaritan, but a second example is the 1970s Coca-Cola commercial featuring NFL football player “Mean” Joe Greene and a young child (with the bridge divide being the racial issues in America at the time).

Here’s that Coca-Cola commercial as a reminder.

This well-known 1970s Coca-Cola ad tells a simple story that involves bridging several gaps (racial, age group, pro athlete and “normal person,” etc.).

Stories: You Can Find ‘Em, You Don’t Have To Make ‘Em All Up Yourself

But perhaps the most important note about common story plots that the Heaths share is that you don’t have to make up your own stories. Instead, if you know some common story plots, and in particular the three that they’ve identified as often having the ability to inspire people and create action, all you’ve got to do is recognize good stories that fit the mold when you hear them.

As the book notes:

“The goal of reviewing these plots is not to help us invent stories. Unless you write fiction or advertisements, that won’t help much. The goal here is to learn how to spot the stories that have potential.” [Source: see note 22]

So when you run across a good story, and if it reinforces you key training message, and if you recognize it as having the potential to inspire behavior changes and action, try to fold it into your training.

Note: The Heaths three plots above are good, but know there are other lists of common plots out there as well, such as the seven basic plots. So take advantage of the Heaths research on their “big three,” but don’t ignore others.

Stories Encapsulate All Other Methods

The final point that the Heaths make in their book is that stories are so effective partly because they often automatically include the other elements in their six-step, SUCCES(s) method of creating stickiness.

Here’s how they wrap it up:

“Stories can almost single-handedly defeat the Curse of Knowledge. In fact, they naturally embody most of the SUCCESs framework. Stories are almost always Concrete. Most of them have Emotional and Unexpected elements. The hardest part of using stories effectively is making sure that they’re Simple–that they reflect your core message. It’s not enough to tell a great story; the story has to reflect your agenda…

Stories have the amazing dual power to simulate and to inspire. And most of the time we don’t even have to use much creativity to harness these powers–we just need to be ready to spot the good ones that life generates every day.” [Source: See note 22]

So with that, keep your eyes peeled for good stories that support your core training messages.

For more on this, see our interview with Anna Sabramowicz about storytelling and training.

Conclusion: “Sticky” Training Workers Will Remember

We hope you enjoyed this article. We found it fun to write, to be honest.

More importantly, we hope you’ve learn some new techniques to make your training more memorable and to make employees more likely to use take that training and use it on the job. And we hope we’ve inspired you to do just that–incorporate these six elements into your training. Or consider getting memorable, visual online workforce training from us (short sample below).

Although we do help this article was a good start for you, we still highly encourage you to pick up and read a copy of Made to Stick as well. There’s a whole lot more that the book has going for it than what we covered in this article. It’s well written, it’s funny, it’s got many spot-on examples from different walks of life, it’s got a handy “Easy Reference Guide” at the end, it’s got a nice notes section that includes many references to the academic sources they reference, and there’s a lot more to say on its behalf as well. Sounds like we’re trying to set you up on a blind date, huh?

Now, in closing, what are your own thoughts? Have you read the book? If so, did you like it? Have you tried using some of these techniques in your own training, either after having read the book or for some other reason? How did they work? Are there other tips that you’d add to these six? Any recommendations for other trainers out there trying to improve the quality of their own work?

See you with our next article. Until then, let us know if you’d like more information about online training courses for the workplace, or learning management systems (LMSs) for training administration, or custom training solutions. Or if you’d like to set up a demo or preview.

Manufacturing Training from Scratch: A Guide

Create a more effective manufacturing training program by following these best practices with our free step-by-step guide.

Notes:

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, Introduction (I have an ebook that doesn’t display page numbers…this is location 312, if that helps).

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 312

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 450

- Matthew, 19:24, King James translation

- Ezekiel, 18:2, King James translation

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 1129

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 2012

- “The Fox and the Grapes” by Aesop; as reprinted in Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 1524. The second quote was written by the Heath brothers and is at location 1545.

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 1727

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 1775

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 1618

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 2066

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 2150

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 2161

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 2244

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 2612

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 2783

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 3260

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 3280

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 3387

- Lincoln, Stowe, and the “Little Woman/Great War” Story: The Making, and Breaking, of a Great American Anecdote, Daniel R. Vollaro, The Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, accessed on 5/26/2016 at http://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0030.104/–lincoln-stowe-and-the-little-womangreat-war-story-the-making?rgn=main;view=fulltext. Vollaro’s point that Lincoln may never have said this is interesting but beyond the scope of this article and irrelevant to the discussions of the power of the novel; in fact, what it DOES do is support the power of storytelling ,with the possibly apocryphal story being yet another example.

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 3578-3651

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 3651

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip & Dan Heath, location 3755

Highly informative, thought-provoking and really inspiring article. Any trainer will immensely benefit, if s/he decides to use these factors while preparing the Training Content and ultimately delivering it to the target Audience. Thank you for this useful write-up.

Ameer, glad you liked that article, and thanks for the nice words. The book is a very fun read; if you have time and the inclination, I recommend it. Have a great day.

Really enjoyed your article/synopsis of the book. Some wonderful training advice!

Lynne, thanks for the kind words. The book is a fun read–hope you pick it up one day. Have a good one.

It is great article and reminder for the professional who presents more often!

Thank you for sharing your knowledge and experience in wonderful article!

Toral, glad you found something of value. Have a great day.

Amazingly well thought article with lots of “sticky” material for trainers and communicators to use. Thank you!

Cheryl, glad you found something of value. Hope you continue by reading the book-recommended. Also, stay tuned for blog post coming soon on storytelling, scenarios, and training.