If you’re a trainer or design instructional material, your job is to train people.

But what exactly are you training them? What kinds of things? If your initial answer is “stuff for work,” we can dive down a little deeper on that. The benefit of doing so is that once we realize that we train people on different kinds of “stuff for work” (or to speak a little more formally, we train people to help them with different types of learning), you can get a little more efficient and use different training techniques for each of those different types of learning that you want your employees to master.

That’s what we’re going to cover in this blog post. So if that sounds spot-on, continue reading. If you’re not quite sure how you feel about it, keep reading nonetheless, if you can spare the time. You just might find some tips to make the training programs at your workplace more effective and efficient.

- Learning Management Systems

- Online Workforce Training Courses

- Incident Management Software

- Mobile Training Apps

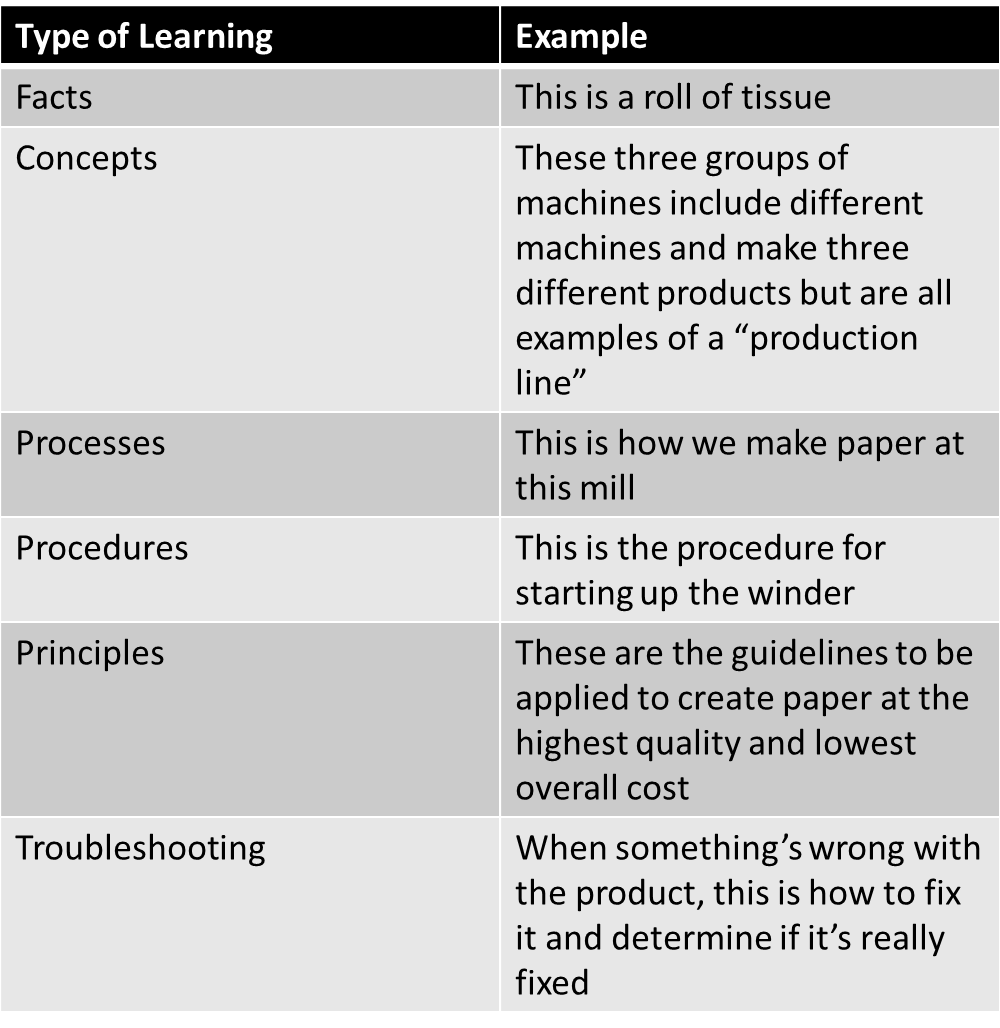

Different Types of Learning

Let’s start by giving some thought to some different types of learning.

Different Types of Learning-Listed

So, let’s go back to that earlier discussion of teaching workers, and wanting them to learn, “stuff for work.”

Obviously, you know that’s such a crude phrase it’s silly. You can break that down immediately, right? For example, you’d probably agree that there are things that your employees have to “know,” and other things that they have to “know how to do.” Right? So if our goal is to start teaching out the different types of learning, we’ve got a little start already.

But we can go even deeper, breaking that down further.

How do these types of learning strike you?

- Facts

- Concepts

- Processes

- Procedures

- Principles

- Troubleshooting

We’re going to spell each of these types of learning out for you in the sections below, but take a moment to review the list right now by yourself. Do you know what each of these are? Can you come up with an example of each? Can you think of times when you’ve tried to help workers learn each of them?

A note about sources: We’re not just typing out free associations here. As Newton said in his famous letter, we’re “standing on the shoulders of giants” in presenting this information. Many of these ideas originated with M. David Merrill’s Content-Performance Matrix. That original idea has been worked with and fleshed out by Dr. Ruth Colvin Clark in her books Developing Technical Training and Graphics for Learning and by Wellesley R. Foshay, Kenneth H. Silber, and Michael B. Stelnicki in their book Writing Training Materials that Work (plus of course elsewhere). These are the primary sources for this article (both Clark and Foshay/Silber/Stelnicki seem to begin with Merrill as a starting point; later, there are some places where they seem to call items from Merrill by different words, but I’ve “merged” those for simplicity, and still later, Foshay/Silber/Stelnicki add a “troubleshooting” level that perhaps extends beyond what Merrill and Clark talk about but could be considered an extension of “principles”).

Different Types of Learning-Defined

Now let’s take a closer look at those different types of learning. Here’s a list of the kind of things you’ll probably want your employees to learn, with an example of each.

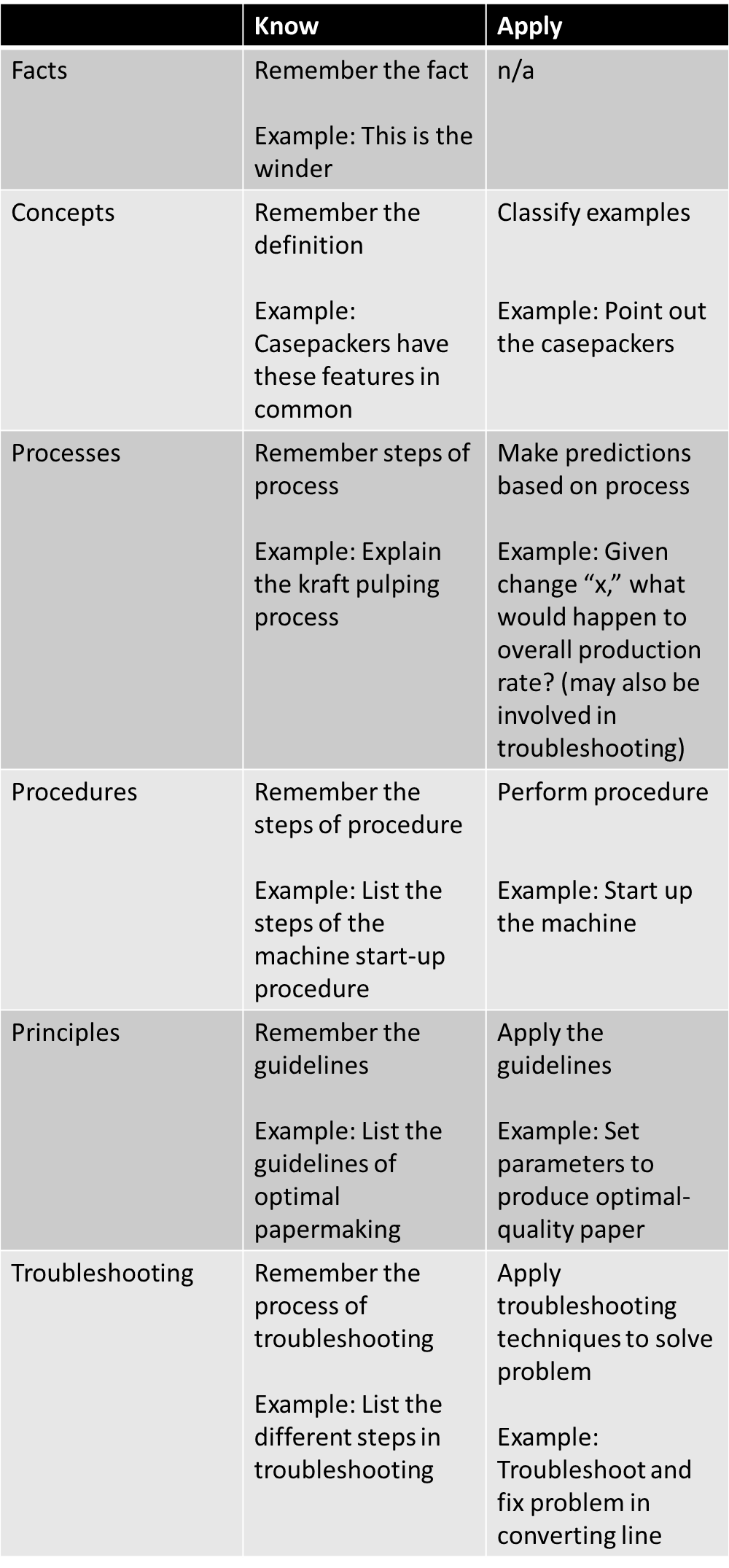

Training to Remember and Training to Apply

One way to look at training people is you can train them to “know” things and/or training them to “use” or “apply” that knowledge on the job.

When it comes to facts, you’ll train people because you want them to know the facts. So you’ll want them to be able to prove they remember the facts by having them repeat, list, or state them.

When it comes to the other types of learning, you want them to “know,” but when it comes to on-the-job performance, you want them to be able to apply that knowledge. So that’s what you’ll be trying to teach them, what you should let them practice, and what you should assess their learning–by having them apply it in a realistic way, like they would on the job.

Here’s a table to help explain that better.

Matching Training Methods to Learning Types

Now that we’ve identified the six different types of learning listed above, let’s look at some suggestions for how to train your workers for each type of learning.

Training Your Employees So They Can Learn Facts

As Clark notes, “facts are unique, one of a kind information.” (1)

For example:

- This is the Metsko paper machine

- Our goal is to produce tissue paper of X density

- Every week we need to manufacture 300 tons of cardboard

It’s inefficient for the brain to process, store, and retrieve facts, simply because they’re somewhat random. All our brains can do is commit each individual fact to memory. And traditionally, job training programs (and yes, school education too) has tended to rely too much on getting people to remember facts.

Use a Job Aid for Facts When Possible

Instead of having people remember facts, try whenever possible to simply create job aids (or references) that they can refer to on the job and/or during training. For example, if a machine operator needs to enter up to ten different codes into a machine at different times of the day based on different circumstances, don’t try to teach the operator to remember all the codes. Instead, during training, provide a list of the codes and teach the operator to enter them at the correct times. Likewise, provide a job aid that includes a list of the codes at the spot in the work area where the operator needs to enter them.

Tips for When it’s Necessary to Train Learners to “Know” Facts

In some cases, a job aid won’t cut it and you will have to provide some training to your workers on the facts themselves. Below are some tips from Clark’s book:

Use Diagrams for “Concrete” Facts

A “concrete” is something unique and specific; Clark’s example is the 1040EZ tax form (which is distinct from the concept of “tax forms”). Another example might be “this is the off button for the bagger.” One way to train your workers to identify concrete facts like this is to include a diagram with labels. For example, imagine a diagram of that bagger, with various parts, including the off button, labeled.

Use Tables and Lists for “Data” Facts

Present data, such as specifications about machine operating conditions, in the form of a list or table instead of embedding it in a normal written paragraph. Presenting data in this manner makes it easier to scan and process.

Use Sentences and Labels in Written Training Materials When Presenting Facts that Associate Two Concepts

In some cases, a fact might create an association between two concepts. A simple example might be “great white sharks are the apex predators in California’s Red Triangle region.” A more work-focused example might be “ideal operating conditions for paper machines is to run between 85 and 95 percent peak efficiency.”

In that example, present the fact in written materials with a label and then the fact in sentence form. Like this:

Ideal Operating Conditions: Paper machines should run at 85-95 percent capacity for ideal operating conditions.

Ask Employees to Derives Rules and Guidelines for Facts During Training

Stop and think of it. Facts presented in lecture format during training can put your employees to sleep pronto. “This is a winder. This is an accumulator. This is a log saw. This is a wrapper. This is a bundler. Etc…”

Instead of presenting facts in such a dry manner that presents information passively to your learners, try turning the tables so they’re active participants in their training.

Here’s Clark’s example: “…show an illustration of two or three sales tickets and ask, “What three items must be included on all sales tickets?” (2)

And here’s a different example: Show six rolls of paper towel–three rolls that pass QA test and three rolls that don’t. Then ask the students to list 2-3 characteristics of acceptable paper towel rolls.

Provide Plenty of Practice When Training on Facts

Because facts are somewhat random and the brain therefore processes them inefficiently, you’ll want to provide lots of practice for using facts during your training.

Clark recommends four different methods of doing this:

- “Weave” factual information into training–If you’re training employees to perform a skill task, and performing that skill or task requires some set of factual knowledge, provide the employees with some reference of those facts (like a written document with the facts written down at their desk) that they can use during training.

- Use a factual reference during training–If you’re training employees to perform a skill to task, and they’ll be able to refer to a job aid when performing the skill or task on the job, then have them practice using the job aid during the training too.

- Drill and practice (consider e-learning for this)–In some cases, you won’t be able to provide a job aid for the worker to use in the field. Maybe it would create a safety risk, either because it would distract the worker from a critical task at hand or because the information needs to be retrieved in a split-second. In that case, old-fashioned drill-and-practice can help people “automate” their retrieval of facts. As a kid, I learned the multiplication tables with flash cards. Now e-learning courses are a more efficient way to do it. But let’s not kid ourselves–this can get boring. As a result, Clark suggests trying to embed the drill and practice into some form of game (search the Internet for “gamification and learning”–it’s a big thing these days).

- Use mnemonic devices–It can be easier to remember a fact if it’s somehow associated with something else in your brain. As a kid, you may have learned the mnemonic devices “every good boy deserves fudge,” “Dumb King Phillip Came Over from Germany Swimmingly” (I know, “dumb” isn’t very nice), and “ROY. G. BIV.” Quick test–do you remember what these mnemonic devices stand for? If so, then that’s a testament to the power of this technique. When you can, try to create your own mnemonic devices to help your learners associate one fact with something else they know.

Assessing Learners on Factual Information

You rarely or never want to train someone a fact for its own sake. For example, you wouldn’t teach your learners what the bundler is just so they’ll know. Instead, you teach them what they bundler so is they can go to the bundler and begin operating it at the start of their shift.

Or, to make the point more directly, you’ll typically teach knowledge-based stuff like facts so that people can use those facts while performing some task on the job.

As a result, it’s not so important to test your employees on the actual facts. Instead, test their ability to perform the skill or task that you want them to perform on the job. If they can do it, then they know the facts well enough.

For additional information about specific types of graphics or visuals to use when training employees about facts, see our How to Create Graphics for eLearning post.

Using Performance Support & Job Aids for Facts

Remember in some cases, it’s easier to not train workers to remember a bunch of facts but instead to give them access to the facts through some form of job aid they can quickly reference where they need the information on the field, such as with the mobile training & job support app shown below.

Training Your Employees So They Can Learn Concepts

One way to think of concepts is that they’re nouns. Or, in other words, they’re a set of things that share a number of critical characteristics. In Clark’s example, she says that all chairs are intended for sitting and have a back, a seat, some form of support from the floor (3). In a more work-related example, all palletizers have a way to put an empty pallet into place, stack product onto that pallet, remove the pallet when it’s full, and continue the cycle.

Two Types of Concepts

There are two types of concepts:

- Concrete–Things like chairs and palletizers

- Abstract–Things like integrity and efficiency

You’re probably most likely to train people about concrete concepts. It’s OK to train people on abstract concepts, but make sure you really know what you yourself mean (example: how exactly do you recognize “integrity”?).

Learning Concepts to Remember and Learning Concepts to Apply

In some cases, you’ll want your employees to remember concepts, and in others, you’ll want them to to apply those concepts. Let’s see what we mean here:

Remembering a concept--employee can restate the key characteristics. For example, they could restate the three characteristics of a palletizer. However, that in itself doesn’t mean they can identify a palletizer “in the field,” if you will.

Apply a concept–employee can use the remember characteristics to identify the concept. For example, the employee can walk onto the work floor and identify the palletizers.

You typically won’t train workers about concepts just so they can restate the key characteristics (meaning they “remember”). Instead, you’ll want them to apply the concept. In some cases, that’s the task they’ll perform–like, identify defective products and remove them. In other cases, they’ll need to identify one or more concepts in order to complete a procedure. For example, they may have to complete a procedure that involves five different tools or pieces of equipment, and as a result will need to know what each tool or equipment is and does.

Because you’re most likely training workers about concepts because you want them to apply the concept, make sure your learning objective is some form of action: “identify defective paper rolls” or “use machine X, machine Y, and machine Z to perform Task A.”

Training Materials for Concepts

Clark recommends that you provide three things when teaching people about concepts (4). They are:

- A definition–What are the characteristics that are critical to this concept–for example, chairs have back, seats, and a method of supporting themselves from the ground.

- Examples–Different items that are part of this concept–for example, different types of chairs.

- Non-examples–Things that aren’t part of the concept–something that’s closely related but not a match. For example, couches and beds are good non-examples of the concept “chair.”

Analogies for Training about Concepts

Analogies are an effective and helpful way to teach concepts. An analogy is something that’s similar to but different than the concept. Clark gives an example of cutting up a pie into different-sized pieces to explain fractions of numbers. Analogies are helpful because they take something the learner is not familiar with and show how it’s like something the learner is familiar with. As a result, analogies only work when they compare the new concept with something the learner already knows.

Practice for Training about Concepts

Like most all training, your learners will benefit from practice when they’re learning a concept. Because you’ll probably want them to be able to recognize when things “fit” or “don’t fit” in a concept, you should set up scenarios in which they’re given examples and non-examples of the concept and ask them to correctly identify each.

For additional information about specific types of graphics or visuals to use when training employees about concepts, see our How to Create Graphics for eLearning post.

Training Your Employees So They Can Learn Processes

When you train employees about a process, you’re teaching them how something works.

Some common types of processes that Clark describes are (5):

- Business processes–a description of an organizational work flow. Examples include hiring, performance reviews, submitting expense reports, etc. These include steps performed by different people and/or different departments/teams (if it’s something in which all steps are done by one person, it would be considered a procedure).

- Technical processes–a description of the different stages in an industrial, manufacturing, or technical process

- Scientific processes–a description of how natural phenomenon occur (such as lightning or a tornado)

Benefits of Process Training

Employees can benefit from understanding processes for multiple reasons, and understanding how the employee can benefit can help you determine if they need a more superficial, high-level overview or an in-depth, detailed explanation.

Understanding a business process–understanding a business process can help your worker know why the steps he or she must perform are important and/or exactly what’s important in each step (because they’ll know how others later use that). In many cases, you can provide only a superficial overview of a business process–just enough so the person knows how their steps fit into the big picture.

Understanding a technical process–you might want to teach a person about an entire technical process so they’ll know how the part they work on fits, which gives the employee a better chance of creating their part so it “fits in” well–the example that Clark gives in her book is of a computer programmer writing a piece of code that would be added to a larger code base. Another reason Clark mentions, and a key one in many industrial and manufacturing facilities, is that understanding how a process works is key for workers who have to keep that process operating within established productions goals and for others who are responsible for troubleshooting and fixing problems. Finally, having at least a superficial understanding of a work process at an industrial facility may improve overall morale.

Remembering or Applying Processes

You may want employees only to remember a process or know how to apply it.

If your goal is just to make the employee understand a process, then you can keep the training superficial and expect them only to be able to know or explain the process.

If your goal is to have them apply the concept, so their work fits into the overall product or so they can later troubleshoot a process, your training should teach them to apply (not just remember/restate) and you should assess your learners to use the knowledge of the process while applying the process (in troubleshooting, for example).

Presenting Processes During Training

Clark provides the following tips for presenting a process during training with employees:

- If there are facts that the employee must know while learning the process, explain those first. For example, if a process involves multiple machines, including an “accumulator,” begin by telling the names of the machines involved, including the accumulator and explain briefly what it does.

- Explain the process in a combination of words, images, and tables/diagrams/charts.

- Present the process within an orderly chart, diagram, or flow chart, making the order of the different steps clear.

- Images that represent the different stages of a process can be very helpful, especially if there’s some form of visibly apparent “transformation” at each of the steps.

Allowing Practice for Learners

In some cases, it really won’t be necessary to let your employees practice with their understanding of a process. If identifying the different steps of the process isn’t something they’ll need to do on the job, then don’t bother setting up an opportunity for practice. For example, if you’ve explained a process just so they’ll know how the paperwork they create is used by other coworkers in different departments later, there’s no real need for practice.

In other cases, though, your employees WILL need to use their understanding of a process during their jobs. For example, if a maintenance worker has to troubleshoot a system to diagnose and fix a problem, he/she will have to use that process understanding to troubleshoot effectively. In that case, you should set up practice scenarios that allow the employee to practice using the process information to perform the troubleshooting (or whatever else they’d do on the job). Don’t just have them list the steps of the process. (You’ll read more about troubleshooting later in this article.)

Evaluating Employees for Their Mastery of Processes

The same points we just made about practice for concepts applies to evaluating employees’ understanding of processes as well. So, if you want your employees to have a superficial, overview-level understanding of a process just so they understand how their work “fits in,” you probably shouldn’t evaluate them on the process. But, if you do have to evaluate them because they’ll have to use their understanding of the process on the job, then don’t just ask them to list the steps or explain the process, but evaluate them on their ability to perform the task(s) that requires them to understand the process (like evaluate them on troubleshooting exercises).

For additional information about specific types of graphics or visuals to use when training employees about processes, see our How to Create Graphics for eLearning post.

Training Your Employees So They Can Learn Procedures

A procedure is a simple list of task of steps that a worker must complete.

Identifying the Steps/Stages of Your Procedure

It can be a little tricky to correctly identify all the steps of a procedure before you teach the procedure to employees. If you’re not an expert on the procedure, this may be because you don’t know the procedure yourself. If that’s the case, talk with people who know the procedure well, and have them help you identify the steps. It can also be helpful to watch someone performing the procedure in the field, or to video tape them, so you can observe what they’re doing.

Be careful if you’re trying to learn the steps of a procedure from an expert performer. In many cases, experts like this know a procedure so well that parts of it become “automatic” to them. This means when they tell you the different steps, they may leave some out. Again, here’s where watching in the field or videotaping can help.

Identifying Steps for Novices and Steps for More Experienced Workers

When you’re identifying the steps of a procedure, keep in mind the type of employees you will be training and their related knowledge. In some cases, something that’s only a single “step” for an experienced worker will have to be presented as multiple steps for workers who are entirely new to the material. Clark gives a good example of logging on to a computer. For a worker who’s familiar with computers, that’s a simple step in a procedure. But for workers who aren’t familiar with computers, that’s multiple steps (turn on, press Ctrl-Alt-Del, enter username/password, etc.).

Linear and Branching (or Decision-Based) Procedures

While identifying the steps of a procedure, you’ll notice they may be of two types:

- Linear procedures–you do the same steps in the same order every time

- Branching (or decision-based) procedures–procedures that call for employees to make a decision at one or more step, with the future steps being based on the results of that decision. For example, if the procedure is about checking and changing oil, an if one step is to check the current oil level, then the next step will be “re-insert oil dipstick and stop procedure” if the oil level is fine but the next step will be “add engine oil” if the oil level is too low.

Make sure you know what type of procedure you’ve got–linear or branching–before you teach it to employees.

Job Aids for Procedures

Remember that for job training, your goal isn’t normally to have your workers be able to state the steps of a procedure. Instead, you want them to be able to perform the steps on the job. As a result, whenever possible, provide a job aid that explains the steps of the procedure and let them use that job aid during training and even in the field.

Training Workers to Perform Procedures

Clark explains that teaching your workers to perform procedures should include the following:

- A clear explanation of the different steps of the procedure. This can be made more effective if the steps are listed in a table, diagram, or chart, and if the steps are accompanied with a photo, video, or other image.

- A demonstration of how to perform the procedure so the employees can watch it being perform

- An opportunity to practice performing the procedure, so the employees can practice doing it themselves

- Feedback to the learners as they practice performing the procedure, telling them what they’re doing right and what they’re doing wrong. Always provide feedback in a friendly, non-threatening, supportive manner.

Evaluating Your Workers for Procedures

As is true with most of the other content types we’ve talked about (facts are the exception here), your employees can both know and be able to perform a procedure. Knowing means they can list the steps. Being able to perform means they can actually complete the procedure. In almost every case, what’s important on the job is if the employees can perform the procedure.

As a result, you’ll typically want to create assessments that evaluate if your workers can perform a procedure, not just list the steps.

For additional information about specific types of graphics or visuals to use when training employees about procedures, see our How to Create Graphics for eLearning post.

Training Your Employees So They Can Learn Principles

It may help to take a moment to remind ourselves of the difference between a procedure, which we just learned about, and a principle, which we’re about to learn about.

Performing Procedures and Applying Principles

When you train a worker to perform a procedure, you’re teaching them to perform a series of steps in the exact same order every time. The example that Clark gives is a cook at a fast-food restaurant who must prepare a burger the same way every time. Experts in learning and development sometimes refer to procedures as near-transfer tasks.

By contrast, when you’re training a worker to apply a principle, things aren’t going to be the same every time. You want your employee to follow or apply a set of guidelines to apply principles in a number of different circumstances, each of which will be different from the others. There will be no set order or exact duplication of steps. The example Clark gives is a master chef using the rules learned in culinary school to make an entirely different delicious dinner special night after night after night. Another example would be training a salesperson to apply principles to interact with a customer and close a deal–again, the situation will be different every time, and the sales person will have to think on his or her feet and do what’s necessary at each moment to apply the principles within the set of guidelines. Experts in learning and development sometimes call principles far-transfer tasks.

Principles and Guidelines

What you’ll be working with during this kind of training are:

- Principles–cause-and-effect relationships that lead to specific, definable outcomes. For example, during management training, managers-to-be might be told that new employees respond well to assignments that are challenging but not so difficult they won’t be able to meet the challenge.

- Guidelines–A set o f “rules” that, when applied, will help the employee apply the principle as a whole. To return to our “challenge new employees” example above, guidelines might include (1) ask employee what he/she is interested in, (2) determine employee’s current level of knowledge and skill, etc.

Making Sure Your Principles Are Valid

It’s harder, more time consuming, and generally takes more money to train people to follow guidelines and apply principles in shifting, dynamic situations on the job. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to do it–ask any sales manager who’s seen sales increase as a result of sales training. But it does mean we should make sure the principles we’re trying to train are valid.

In short, don’t waste a lot of time and money on training if the ideas you’re pushing are half-baked or inaccurate.

To that point, Clark recommends checking professional literature and observing experts in the field to identify principles and guidelines.

Remembering and Applying Guidelines and Principles

As with the other types of training mentioned above, employees can either remember or apply guidelines and principles. But in most every case, because you want them to apply the principles on the job, you should write learning objectives that require them to apply the principles, provide training for application of the principles, and assess your employees’ learning by evaluating their application of the principles. In general, you shouldn’t be satisfied with whether or not they can restate the principles and guidelines.

Training for Application of Principles

When training your workers to apply principles within a set of guidelines, your training should include:

- Present and explain the principles and guidelines clearly

- Provide demonstrations/examples of the guidelines being applied in different scenarios (make sure to provide these demonstrations within a realistic, work-like environment–as close to the conditions the employee will experience on the job as possible)

- Ask your employees questions about what they see in your different example scenarios, including:

-

- Can they identify which principles are being applied, and when, in each example?

- What do the scenarios have in common? How are they different?

- What worked and what didn’t?

- How could the examples that didn’t work be improved?

-

- Give the employees several opportunities to practice applying the guidelines within different situations in a case-study/scenario-based training format (make sure you’re having employees practice within conditions that are the same as or as close as possible to the conditions they’ll experience on the job)

- Give employees helpful, supportive feedback as they work through their practice scenarios; ask other employees who are also learning the principle to help with assessment/feedback

For additional information about specific types of graphics or visuals to use when training employees about facts, see our How to Create Graphics for eLearning post.

Training Your Employees So They Can Learn Troubleshooting

To discuss training employees to troubleshoot, we’ll rely more heavily on the Foshay/Silber/Stelnicki book, because Clark doesn’t give a chapter to it like she does the other types of learning.

However, before we begin, let’s review a few things Clark does say about troubleshooting in her book:

- In simple troubleshooting scenarios, in which the employee will follow some form of linear or decision-based procedure (the kind that can be diagrammed in a flow chart), you can apply the rules for training procedures listed above. (6)

- Machine/industrial operators will be more effective troubleshooters if they have a better understanding of the technical process used (7)

- It’s fair to assume that a lot of what Clark addresses in the “principles” section could be applied to troubleshooting. In fact, throughout that section, she often uses the phrase “far-transfer tasks,” which is similar to what Foshay/Silber/Stelnicki mean when they use the phrase “ill-structured problem solving” in their troubleshooting chapter.

According to Foshay/Silber/Stelnicki, here are some important notes about troubleshooting in general (8):

- The employee must have a sound grasp on the underlying facts, concepts, processes, and procedures involved in the system they’re troubleshooting

- The employee must being troubleshooting by defining the initial state of the system (the system while it’s experiencing a “problem” of some sort), the goal state (what they want the system to be like when the problem is corrected), and the constraints of the system.

- The process of troubleshooting will be one of identifying all the possible causes, determining which are most likely, implementing solutions and testing to see if they worked.

- It’s important for the employee to reflect on the troubleshooting process after the problem has been solved. This makes the employee a more effective troubleshooter in future times.

Training for Troubleshooting

Given what we’ve explained above, here are tips from Foshay/Silber/Stelnicki to teach workers to be more effective troubleshooters. These tips are for troubleshooting a particular system, but learning to troubleshoot well in general is a skill that can later be applied to other systems.

- Begin by teaching all necessary, underlying facts, concepts, principles, and processes. Presumably, most or all of this would have been taught to the employee before he/she got to the point of troubleshooting.

- Teach the principles of normal and abnormal operation, different possible failure modes, and the possibility of each

- Present troubleshooting method: identify problem space (as described above–current state, ideal state, constraints of system)

- Teach employee to troubleshoot by analyzing various causes of problem, determining likelihood of each, applying test/repair methods, and then analyzing to see if solution worked

- Teach employee value and importance of reflecting on troubleshooting process after solution is discovered

- Demonstrate troubleshooting process in several scenarios to allow employee to watch, observe, and learn from experienced troubleshooter

- Ask employee for input/comments during troubleshooting demonstration

- Provide employee with troubleshooting practice opportunities in realistic scenarios that match as closely as possible the conditions they’ll experience on the job.

You may find this article on scenario-based job training and this article on helping workers develop problem-solving skills helpful here.

Conclusion: Different Types of Training for Different Types of Learning

There you have it. By now, hopefully, you’ve seen that you train people at work on more than just “stuff at work.” Instead, you train them on different types of materials, and these include facts, concepts, processes, procedures, principles, and troubleshooting. And, you’ve now seen that you can tailor your training methods to help your workers master these different types of materials more effectively.

Let us know if you’d like some helpful with workforce training solutions, including a learning management system (LMS) and/or online workforce training courses.

How to Write Learning Objectives

All the basics about writing learning objectives for training materials.

Notes

1. Clark, Developing Technical Training, 106.

2. Clark, , 117.

3. Clark, , 82.

4. Clark, , 86.

5. Clark, , 126.

6. Clark, , 60.

7. Clark, 127.

8. Foshay/Silber/Stelnicki, Writing Training Materials that Work, pp. 153, 130-135.

Nice and insightful work on the facets of training based upon need.

I always enjoy reading your posts …… because I read them, I have a better understanding of what is needed to get the information delivered. Thanks. Ken Rogus

Ken, glad you found some value/interest in it. Thanks for the kind words.

In this case, the real credit goes to the author of the book I’m discussing–Dr. Ruth Colvin Clark. I really enjoy her work and have read a handful of her books by now–they’re very helpful. We’ve also now recently written a blog post looking at training graphics that’s based on a different book of hers (along with yet another existing post about training graphics based on a book by Connie Malamed, another favorite). And you’ll be seeing at least one additional post about training graphics based on Clark’s book as well.

Cheers,

Jeff

Really useful summary of the different content types and how they should be handled when designing a learning resource. I think this type of analysis is often skipped or simply missed when content is being developed, resulting in a sub-optimal learning experience and failure to meet the required business need.

Mark, we’re glad you found something useful there (all credit to Dr. Ruth Colvin Clark), and I agree with your point above. Have a great day.

This information was very well organized and explained with great examples. As I read through the various types of learning, I couldn’t figure out where communication skills would fit. If there is a process to the communication (e.g. conflict resolution or persuasion) it would make sense to use the process learning but what about communication skills that are based on context, such as microskills in counseling?

Good questions, Alayna.

I have to admit I don’t consider myself an expert on communication skills training, although it’s an important topic for sure. But considering the types of learning here, it’s somewhat similar to “ill-structured problem solving,” right? You have to learn general principles and then figure out how to apply them in diverse circumstances. Sound true?